Kufr Aur Kafir Shabd Ki Vastivikta

March 31, 2016

‘We Will Not Be Victims’: Amirah Aulaqi and Mariana Aguilera

April 1, 2016Meet the Empowering Woman Behind Hijabis of New York

Earlier this week, Dolce & Gabbana announced that it would soon release its first collection of high-fashion hijabs and abayas, the modest headscarves and cloaks worn by some Muslim women. The news broke just months after London’s Mariah Idrissi became the first hijab-wearing model to be featured in an ad campaign for H&M; meanwhile, online stores like Hijab-ista, Haute Hijab, and Hijab Chic have long existed as digital marketplaces for young, fashion-conscious Muslim women across the globe.

Still, despite the progress made in recent years, headscarves remain a point of heated debate in the U.S. and abroad, and covered women are often labeled as being either docile  or oppressed, regardless of their personal reasons for donning the garments. In the hopes of breaking down such stereotypes, Rana Abdelhamid, a 22-year-old Queens native and graduate student at the Harvard Kennedy School, started the social-media project Hijabis of New York in the fall of 2014. Using photos and interviews in the style of Humans of New York, the campaign has since garnered more than 19,000 fans on Facebook. The project, also viewable on Tumblr and Instagram, aims to empower hijab-wearing women in the five boroughs while educating the general public on what it means to be young, Muslim, and female in post–9-11 America.

or oppressed, regardless of their personal reasons for donning the garments. In the hopes of breaking down such stereotypes, Rana Abdelhamid, a 22-year-old Queens native and graduate student at the Harvard Kennedy School, started the social-media project Hijabis of New York in the fall of 2014. Using photos and interviews in the style of Humans of New York, the campaign has since garnered more than 19,000 fans on Facebook. The project, also viewable on Tumblr and Instagram, aims to empower hijab-wearing women in the five boroughs while educating the general public on what it means to be young, Muslim, and female in post–9-11 America.

“Basically, we want to diversify and elevate the narrative surrounding Muslim women,” Abdelhamid tells the Voice. Calling from John F. Kennedy International Airport, she’s moments away from boarding a flight to Madrid, where she’ll meet with the local chapter of the Women’s Initiative for Self-Empowerment (WISE), a self-defense and leadership organization she originally founded for young Muslim women in New York City. “Now we have the language to speak about these issues. We have blogs that elevate Muslim women and elevate [hijabi] fashion. So there has been a trend.

John F. Kennedy International Airport, she’s moments away from boarding a flight to Madrid, where she’ll meet with the local chapter of the Women’s Initiative for Self-Empowerment (WISE), a self-defense and leadership organization she originally founded for young Muslim women in New York City. “Now we have the language to speak about these issues. We have blogs that elevate Muslim women and elevate [hijabi] fashion. So there has been a trend.

“It’s a product of social media and a product of having access to these types of resources that allows us to convey our own narrative,” Abdelhamid adds. “It’s really empowering.”

At the age of sixteen, while on her way to volunteer at a domestic-violence shelter in Jamaica, Abdelhamid was attacked by a man on the street who attempted to forcibly remove her headscarf. She remembers struggling to break free of her assailant’s grip, the broad-shouldered man looking down at her with anger and hate in his eyes. After running to safety, she locked herself in a bathroom and cried, traumatized by the experience.

A black belt in shotokan karate, Abdelhamid founded WISE as a means of emboldening young Muslim women facing similar threats of violence and Islamophobia in New York. In 2015, following reports of growing anti-Semitism around the world, the organization expanded its purview to include Jewish women.

A black belt in shotokan karate, Abdelhamid founded WISE as a means of emboldening young Muslim women facing similar threats of violence and Islamophobia in New York. In 2015, following reports of growing anti-Semitism around the world, the organization expanded its purview to include Jewish women.

“I was doing research, and after 9-11 hate crimes against Muslims had increased by 1,600 percent, according to FBI statistics,” Abdelhamid says. “I was like, ‘OK, look, I’m not alone in this. There must be other people [like me] out there.’ ”

Abdelhamid’s family immigrated to Queens from Egypt two years before she was born. Abelhamid was raised in Astoria; her family now resides in Flushing.

The inspiration for Hijabis of New York was the result of a slow, simmering frustration from years of insensitive  comments made by classmates and acquaintances. Though Abdelhamid credits Queens as being one of the most culturally diverse areas in the world — and the city as a whole continues to enjoy a reputation as a bastion of liberalism — New York after 9-11 was not an easy place for a young Muslim girl in a headscarf to grow up. Even as an undergrad at Middlebury College in Vermont, Abdelhamid found that her peers would often pose questions that left her scratching her head.

comments made by classmates and acquaintances. Though Abdelhamid credits Queens as being one of the most culturally diverse areas in the world — and the city as a whole continues to enjoy a reputation as a bastion of liberalism — New York after 9-11 was not an easy place for a young Muslim girl in a headscarf to grow up. Even as an undergrad at Middlebury College in Vermont, Abdelhamid found that her peers would often pose questions that left her scratching her head.

“I was receiving a lot of questions from my classmates about my hijab, and a lot of them came from just a lack of understanding. Not malicious at all, but they were silly questions,” she explains. “One of my friends was like, ‘Gee, Rana, when I first met you I thought you’d be different, like, more quiet. But you’re actually pretty normal.’ I was like, ‘What!?’ ”

Abdelhamid and the other young women featured on Hijabis of New York are normal, of course. Some of the questions featured on the page do deal with Islamic faith, devotion, and (naturally) the hijab, while others read like something one might ask any stranger on the street, regardless of religion or cultural background. When asked how she’s able to see positivity in life, one woman, while eating at the Halal Guys food truck on 56th Street, shares that as long as her hijab is “on fleek,” she’s happy. Another girl jokes that she likes to “Netflix and chill” in her spare time. Others go deeper into how wearing a headscarf has affected their lives and faith practice, as well as some of the challenges young Muslim women face given the often xenophobic rhetoric of today’s political landscape.

of religion or cultural background. When asked how she’s able to see positivity in life, one woman, while eating at the Halal Guys food truck on 56th Street, shares that as long as her hijab is “on fleek,” she’s happy. Another girl jokes that she likes to “Netflix and chill” in her spare time. Others go deeper into how wearing a headscarf has affected their lives and faith practice, as well as some of the challenges young Muslim women face given the often xenophobic rhetoric of today’s political landscape.

“[Muslim women] who wear the hijab are also individuals,” explains Linda Sarsour, a local racial justice and civil rights activist whom the New York Timesdubbed a “Brooklyn homegirl in a hijab” in a profile last year. “We’re not a monolith. We have different aspirations and we come from different backgrounds and I think [Hijabis of New York] kind of describes that in a way that’s important.”

Sarsour was 21 when the World Trade Center was attacked on September 11, 2001; she had been wearing the hijab for roughly a year. She was able to see the shift that happened in the weeks, months, and years following the attacks — a not-so-subtle transformation in the way her fellow New Yorkers came to view her presence in the ci ty.

ty.

“Young people, like the ones that are in [Hijabis of New York], only know a post–9-11 America — they were like two when 9-11 happened,” Sarsour says. “They don’t know a time in this country when American Muslims might have been under the radar, or when it felt a little bit more normal to be an Arab American or a Muslim or a South Asian.

“They were born in a country where being Muslim is not actually a good thing,” she continues. “That’s the scary part: the impact that it has on young people.”

Abdelhamid says wearing a hijab has become part of her identity, and she sees the headscarf as an esse ntial component to her faith practice and spirituality. Though New York continues to suffer its bouts of Islamophobia, she believes the city is moving toward progress. On Thursday, the NYPD settled two lawsuits stemming from its surveillance of Muslims after 9-11, and an independent civilian lawyer will soon be appointed to monitor the department’s counterterrorism practices. “I like to say that I see more good than bad,” Abdelhamid says, “which is why I love New York so much and I want to live here.”

ntial component to her faith practice and spirituality. Though New York continues to suffer its bouts of Islamophobia, she believes the city is moving toward progress. On Thursday, the NYPD settled two lawsuits stemming from its surveillance of Muslims after 9-11, and an independent civilian lawyer will soon be appointed to monitor the department’s counterterrorism practices. “I like to say that I see more good than bad,” Abdelhamid says, “which is why I love New York so much and I want to live here.”

Many of the women featured in Hijabis of New York seem to feel the same way about the five boroughs, despite grappling with the city’s faults.

“I’ve had one pretty bad experience on the train because of how I dress, but nobody here’s been able to hurt me to a point where I had second thoughts about wearing the hijab,” says one woman from the campaign, her head covered and turned toward the Washington Square Arch. “I’d like to think that the average New Yorker will help keep it this way. I love that living in New York City doesn’t stop me from being happy with the way I dress.”

**For Islamic Articles & News Please Go one of the Following Links……

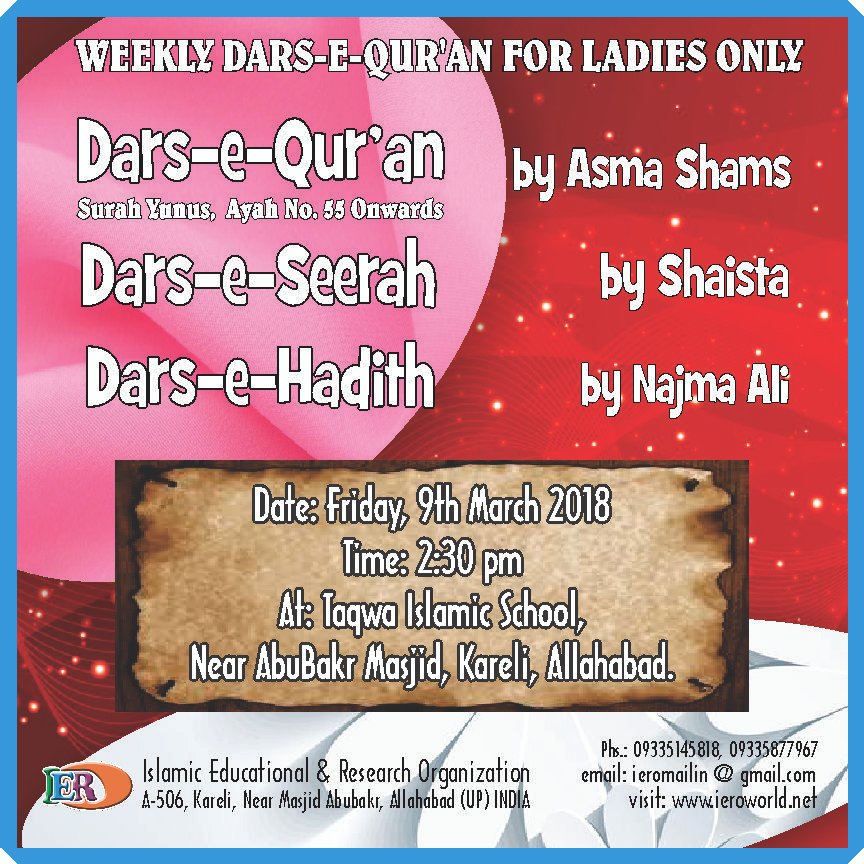

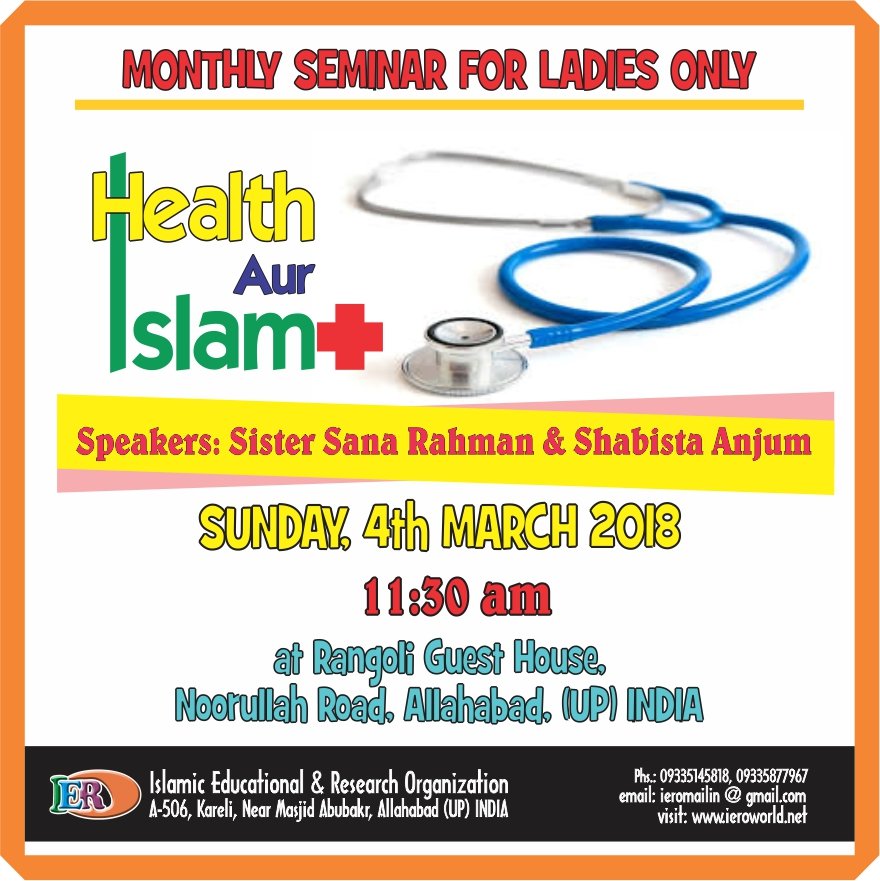

www.ieroworld.net

www.myzavia.com

www.taqwaislamicschool.com

BY JACKSON CONNOR, VOICE

Courtesy :

MyZavia

Taqwa Islamic School

Islamic Educational & Research Organization (IERO)